Michigan Ross Professor Jerry Davis Examines Polarizing Voter Sentiments During First Three Months of the Michigan Ross-Financial Times Poll

Announced in October 2023, Michigan Ross and the Financial Times are partnering on a monthly poll to track how American voters perceive financial and economic issues in the lead-up to the 2024 US presidential election. The poll will run for 12 months leading up to the election.

To access the data referenced in this story, download the spreadsheet here.

The big underlying theme of my questions has been that partisan tribes are living in different worlds with respect to, well, everything. Facts, interpretations, perceived interests, implications for policy — it's like we are characters in a weird novel: The City & the City.

November: Identity trumps economic interests

My top-line takeaway is that these data suggest that identity really does trump economic interests when it comes to how voters think about politics, and this is really significant. For generations, we have believed that property ownership and one's source of income created economic interests, and that these interests drove peoples' political perceptions and attitudes.

In The Federalist No. 10, James Madison stated: “From the protection of different and unequal faculties of acquiring property, the possession of different degrees and kinds of property immediately results; and from the influence of these on the sentiments and views of the respective proprietors, ensues a division of society into different interests and parties.

So, parties are supposed to figure out their voters' (economic) interests and propose policies that serve these interests. This also assumes that people accurately understand their own interests and that they process information (what is happening in the world, perhaps the effects of policies) accurately. There are theories of "pocketbook voting" (I vote directly in my personal economic interests) and "sociotropic voting" (I vote based on how the economy is doing for people like me).

This was adapted by Republicans in the 1990s and 2000s, especially President George W. Bush, to their "investor class" theory: stockholders end up being more economically literate and more attuned to the economic implications of policies, which was the basis of Bush's "ownership society" proposals (see Stock Ownership, Political Beliefs, and Party Identification from the "Ownership Society" to the Financial Meltdown).

But these data show something I have suspected: our brains have been scrambled, and identity is now more important than economic interests in driving perceptions and stated preferences.

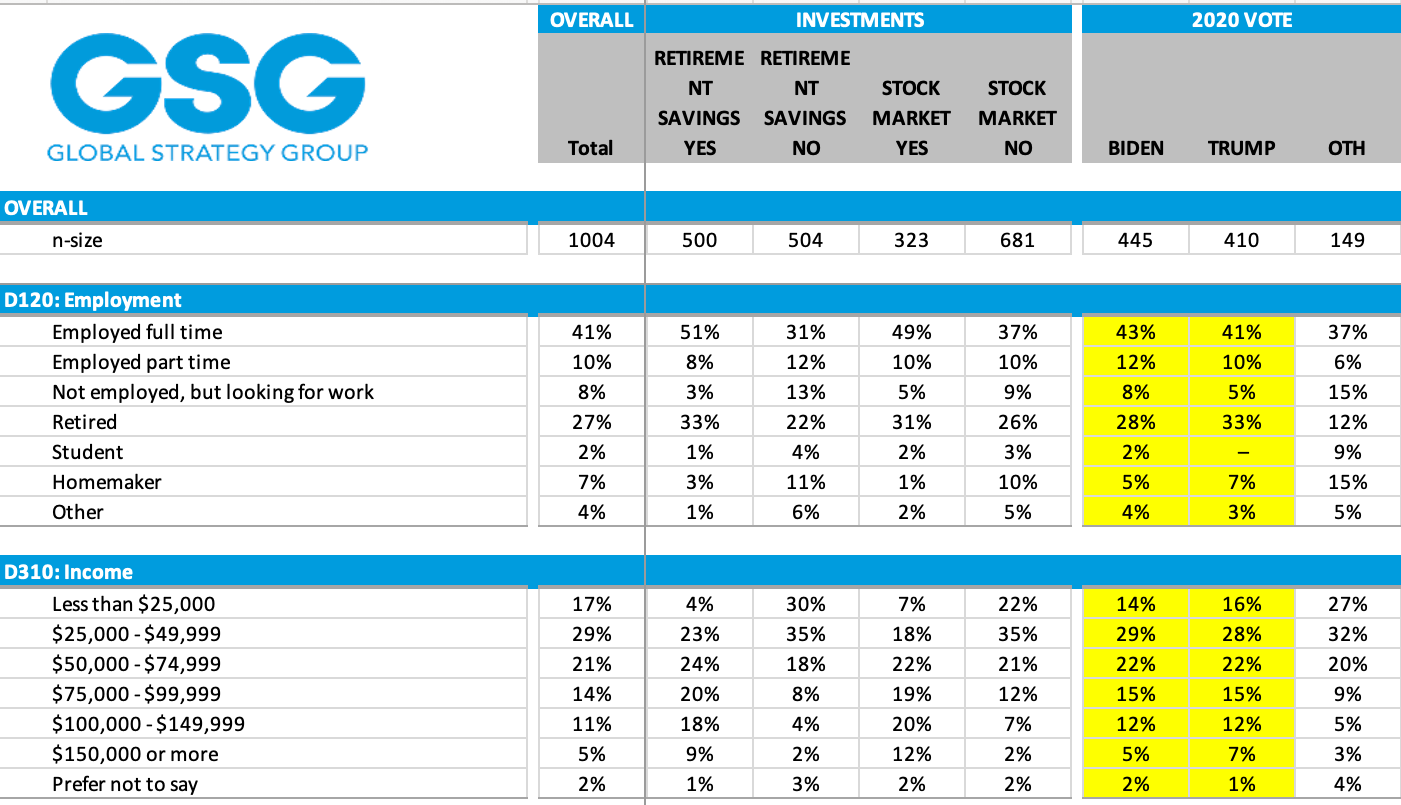

Some evidence: observe that Biden and Trump voters are essentially identical in terms of employment status and income distribution:

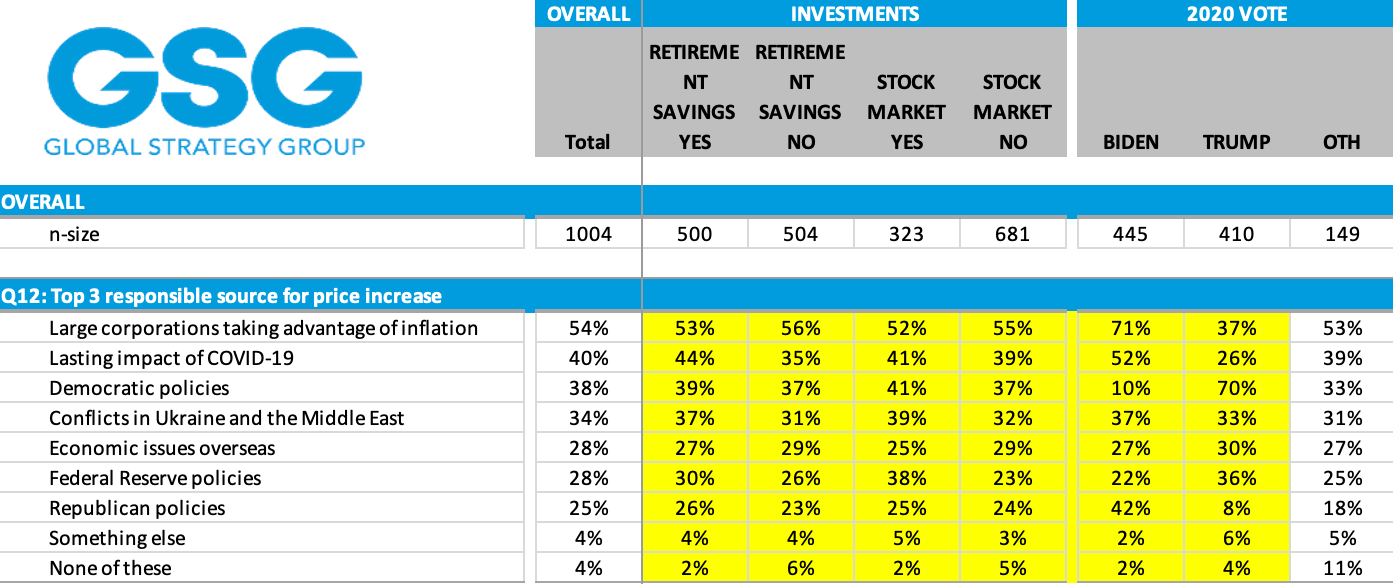

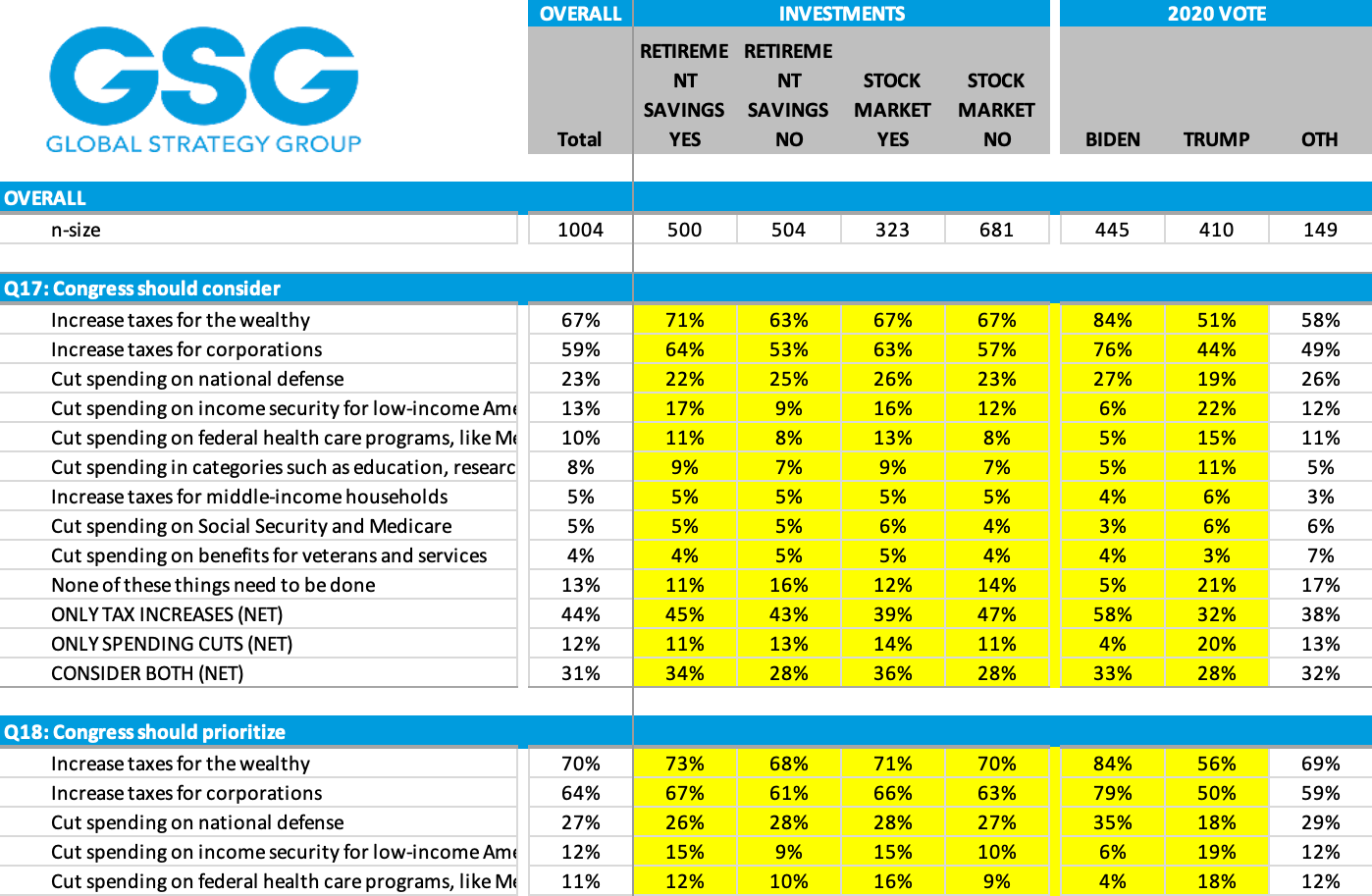

So: economically very similar. Now look at explanations of inflation. Stockholders and non-stockholders (best indexed by "Retirement savings -- yes or no") have very similar explanations. But 71% of Biden voters blame large corporations ("greedflation"), whereas only 37% of Trump voters do:

Similarly, for policy preferences — owners vs. non-owners have similar views on, e.g., raising taxes on the rich, but Biden vs. Trump voters are very different:

December: Why the economic pessimism?

American voters express far more pessimism about the economy than we might expect from the data. This has become particularly pronounced since 2020. The University of Michigan’s Index of Consumer Sentiment – the gold standard for measuring how Americans feel about the economy – normally closely tracks economic fundamentals (inflation, unemployment, stock market returns, consumption).

But since 2020, that model has broken down, and the American public – particularly the Republican part – seems much more negative about the economy than is warranted by objective facts.

Perhaps the problem is that voters are not seeing the same data. We normally imagine that we all can agree on basic facts – things that can be easily verified in under a minute on your smartphone. But what if there is disagreement not just on interpretations of facts, but what the facts are?

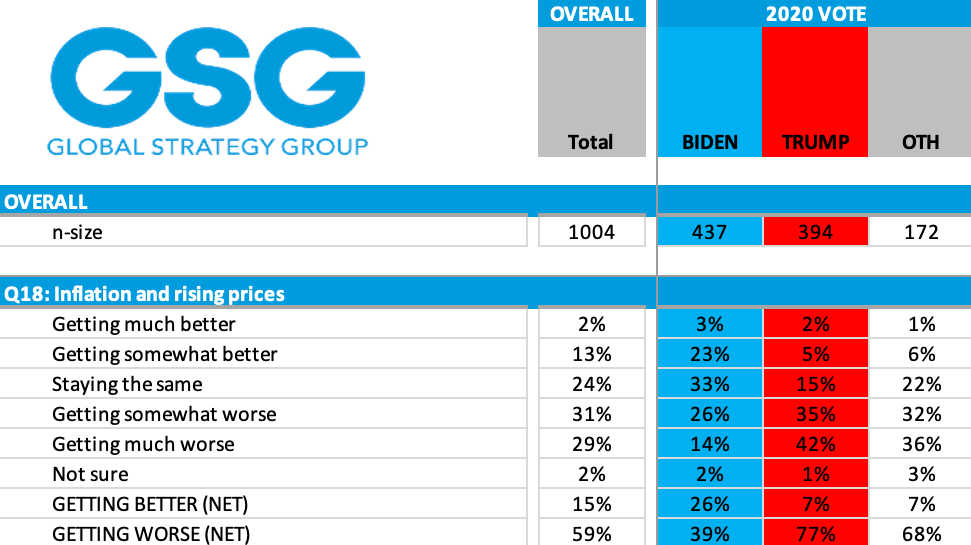

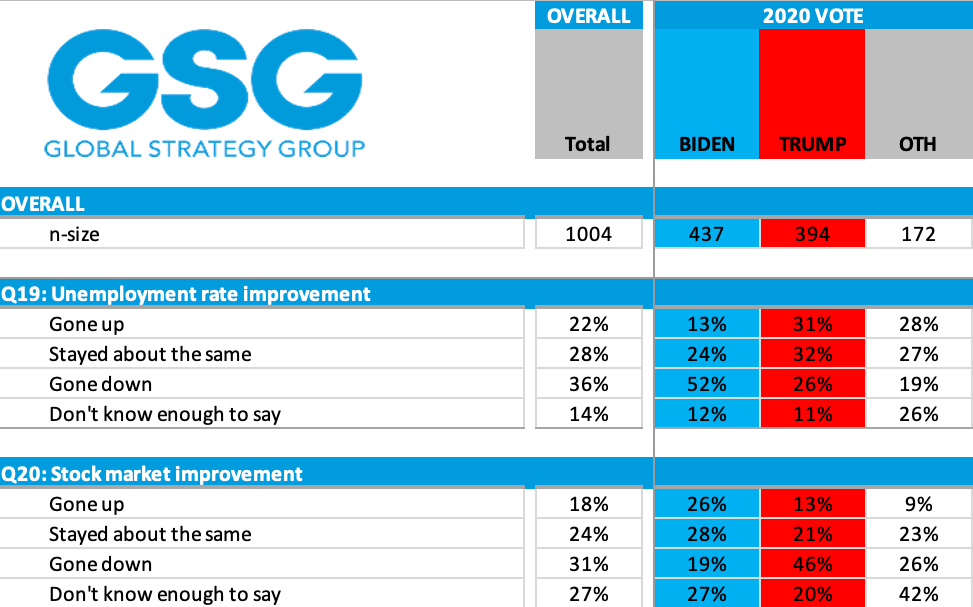

To examine this idea, the FT-Michigan Ross poll asked voters a few factual questions about the economy. The results showed that Trump voters are especially prone to being wrong about how bad things are. The unemployment rate was 6.3% in January 2021 and is currently at 3.9% (a historic low). Yet 31% of Trump voters believe unemployment has increased, and 32% believe it has stayed about the same (compared to 12% and 24% of Biden voters). 77% of Trump voters believe inflation is worsening recently, compared to 39% of Biden voters.

Yet inflation has dropped substantially over the past 18 months. And the S&P 500 has increased 19.6% since Biden took office. Yet 46% of Trump voters believed the stock market has actually declined, compared to 19% of Biden voters.

When partisanship affects not just interpretations of the facts but beliefs about the facts themselves, polarization will not be easy to overcome.

January: What can both sides agree upon?

Republicans claim to experience inflation in a substantially worse way than Democrats, and Independents are in the middle (Q29). So Republicans are like European soccer players, where a slight touch is experienced as a devastating blow requiring medical attention. Not sure what to do with this other than to note that it is consistent with their prior inaccuracies about inflation, unemployment, and the stock market.

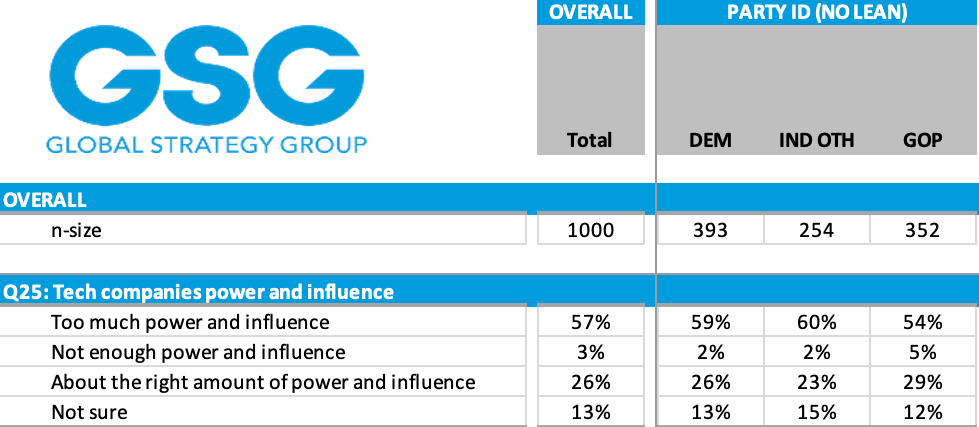

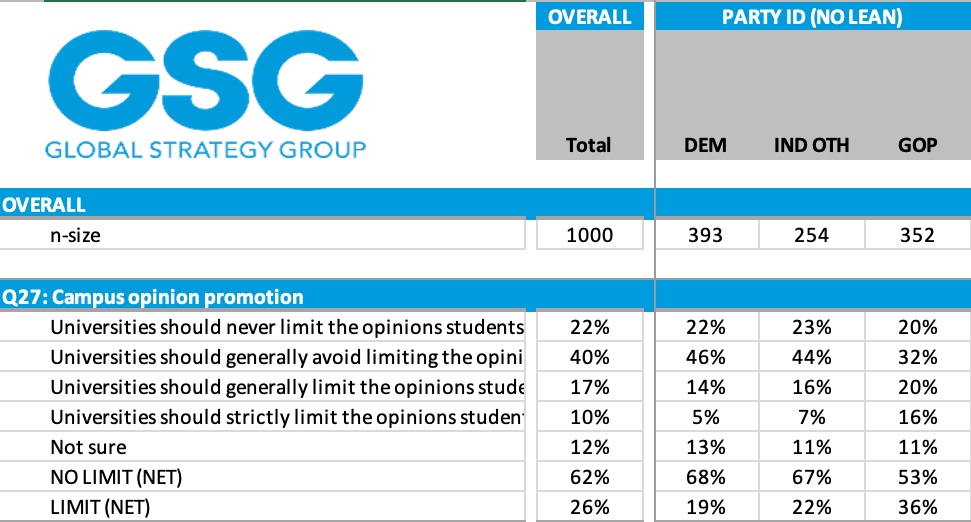

And, it is fascinating that the two main areas of near-uniform agreement are the belief that tech companies have too much power and influence and that universities should not limit the opinions expressed by students and faculty: